Cereal cultivation was a basic survival activity of the Cretan rural population. Before the grain could be sown, the field had to be ploughed to make the soil soft and friable. This was done using the plough (aletri) (1), one of the farmer’s most important tools. The wooden plough has a long, single-piece handle (eheri) and an iron digging blade, the share (yni). Other fittings are the thinner, squared-off wooden mouldboards (paroutia) to push away the soil, and the stavari, the curved beam joined to the base of the plough (podari). At the end of the stavari is the akrostavaro or hitch, which is connected to the iron traces (loura) of the yoke (zygos). For ploughing, the farmer attached the plough to the wooden yoke (2) and harnessed either a horse or a pair of oxen or donkeys by the neck, using the oxbows (zevles). The farmer drove the animals with a sickle-shaped goad (katsounas) (3), which was also used to scrape the plough clean. To soften and level the soil, the farmer used a large, toothed harrow (svarna) (4), adding his own weight to make it more effective.

προηγούμενο

προηγούμενο

info

Πατήστε κάποιο αντικείμενο για περισσότερες πληροφορίες

Click an item for more info

info

Πατήστε κάποιο αντικείμενο για περισσότερες πληροφορίες

Click an item for more info

Wine Press

Wine Press

Πατητήρι

Πατητήρι

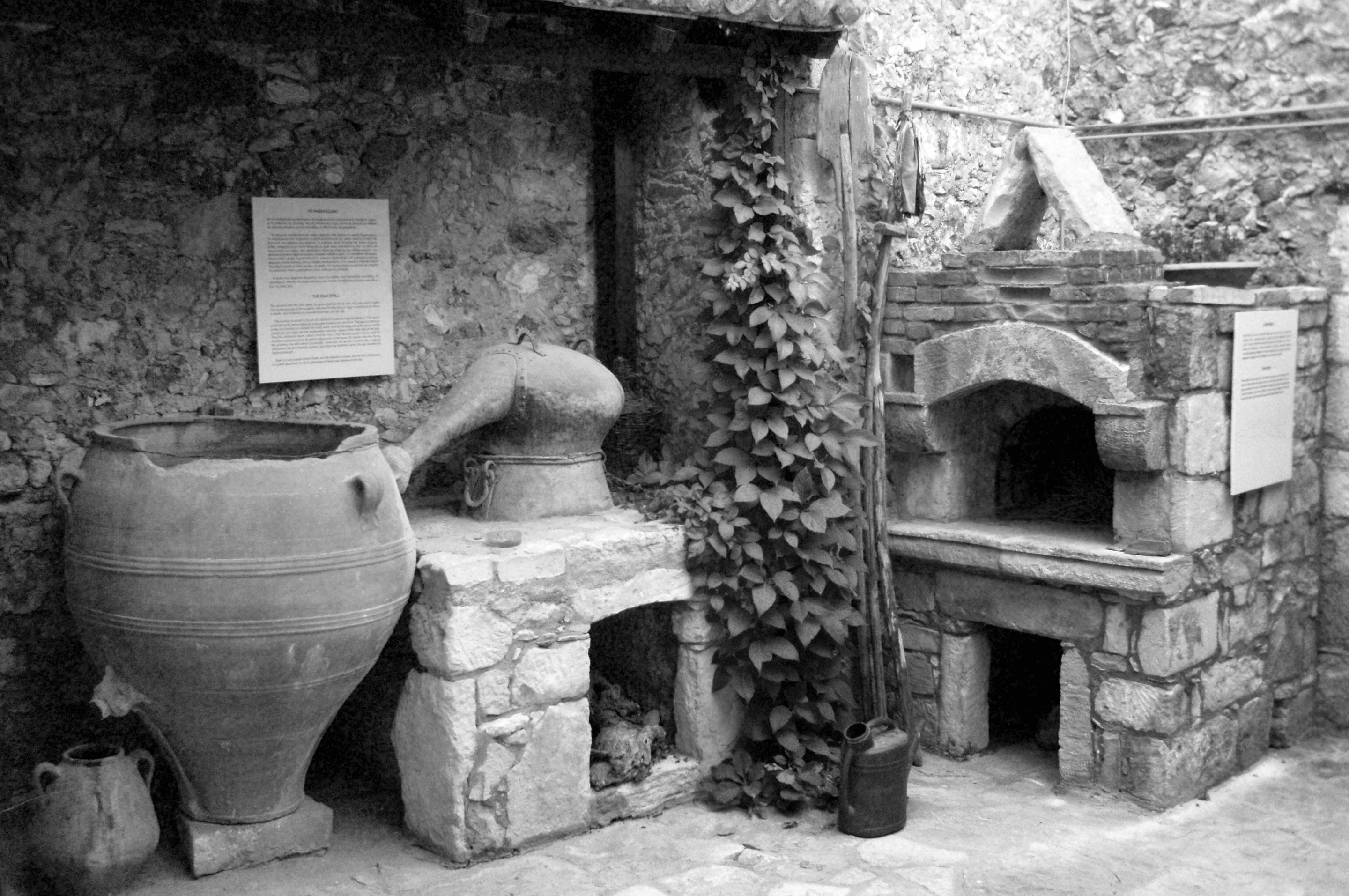

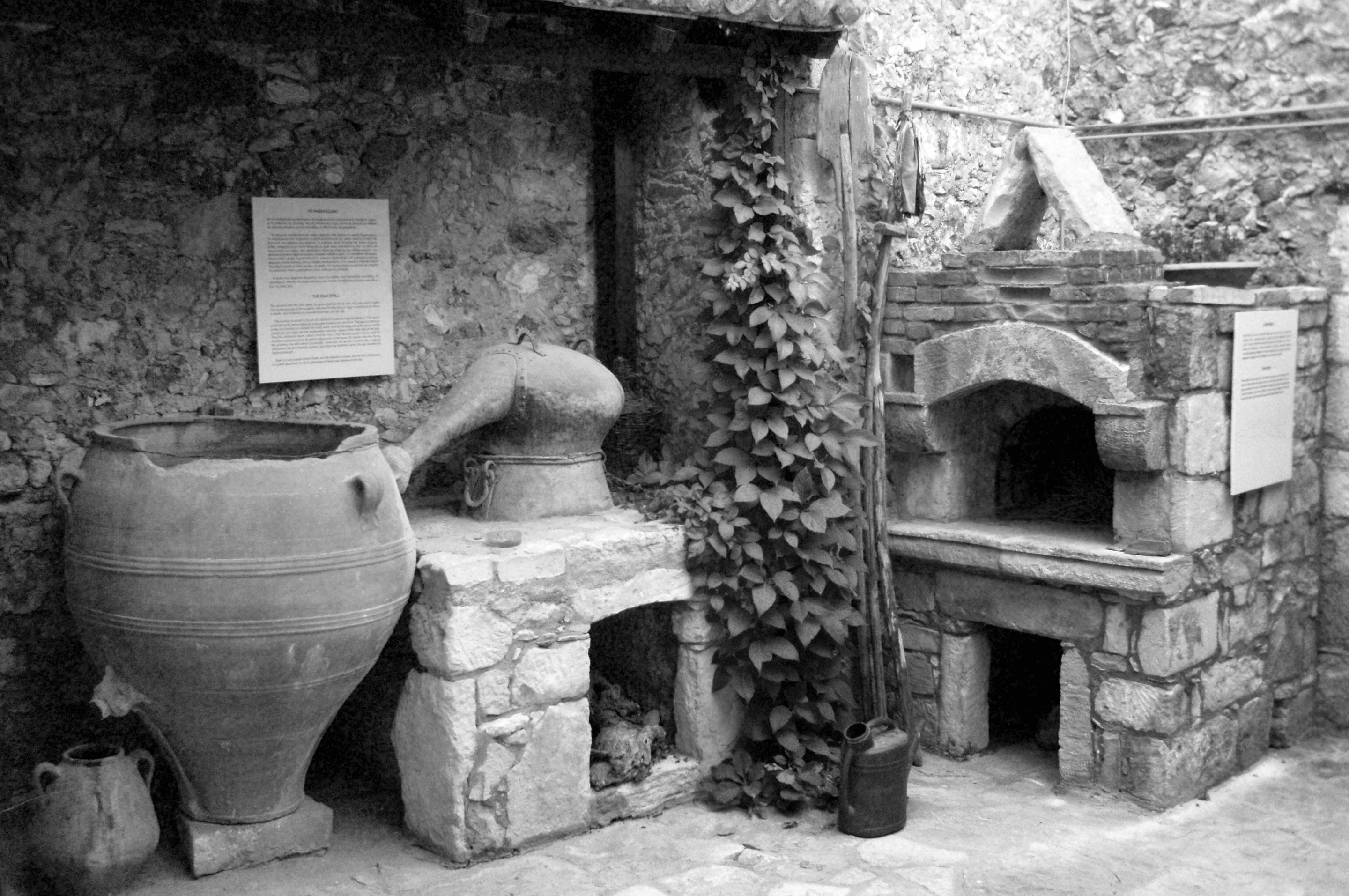

Raki still - Oven

Raki still - Oven

Ρακοκάζανο - Φούρνος

Ρακοκάζανο - Φούρνος

![[object Object]](/img/agrotika-ergaleia/slides/1a.png)

![[object Object]](/img/agrotika-ergaleia/slides/1b.png)